Introducing Narrow Gauge!

Of all the different modeling scales that hobbyists can invest in, HO scale (1:87th) is by far the most popular. An aggregate of different polls conducted over the years shows that while HO scale isn’t quite as dominant as it was twenty years ago, today 60-70% of model railroaders still choose HO scale as their primary modeling scale. However, an increasing number of hobbyists are choosing N scale (1:160) to model in for a few reasons. If you are having trouble choosing, I recently made such a post discussing the issue which you can find here. But one thing I omitted from that article is that there is a third option available to hobbyists who prefer larger trains but don’t have a ton of room for a train layout.

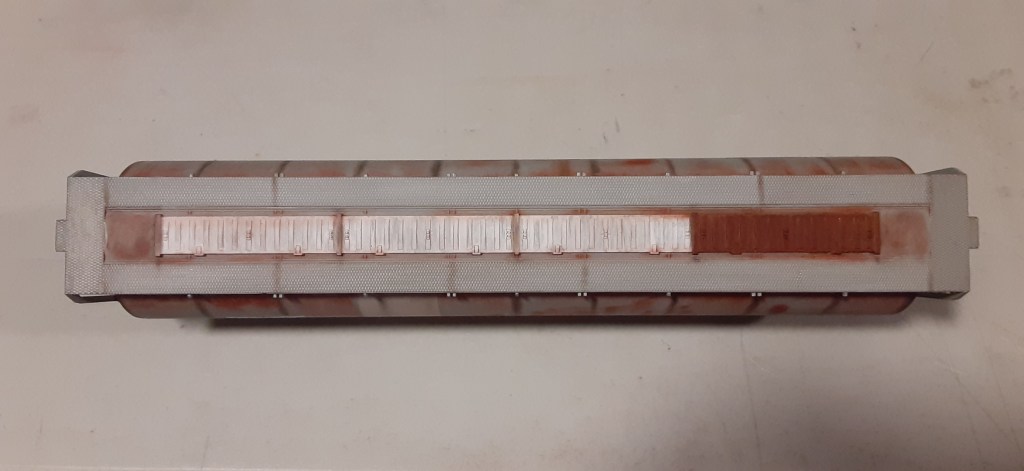

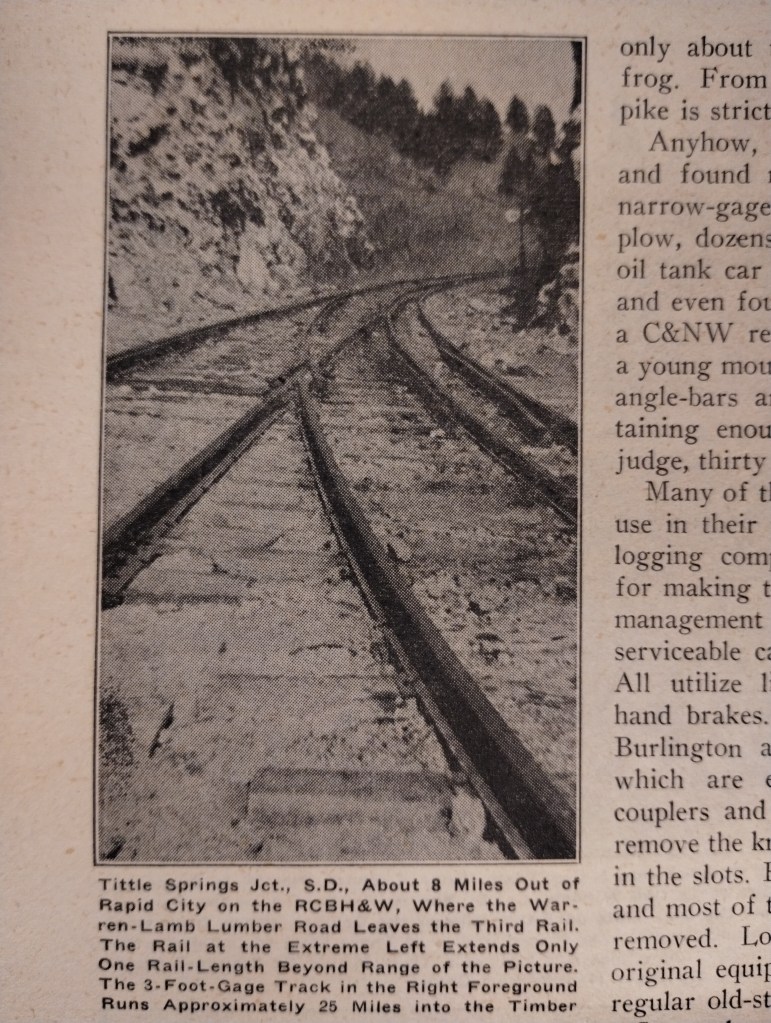

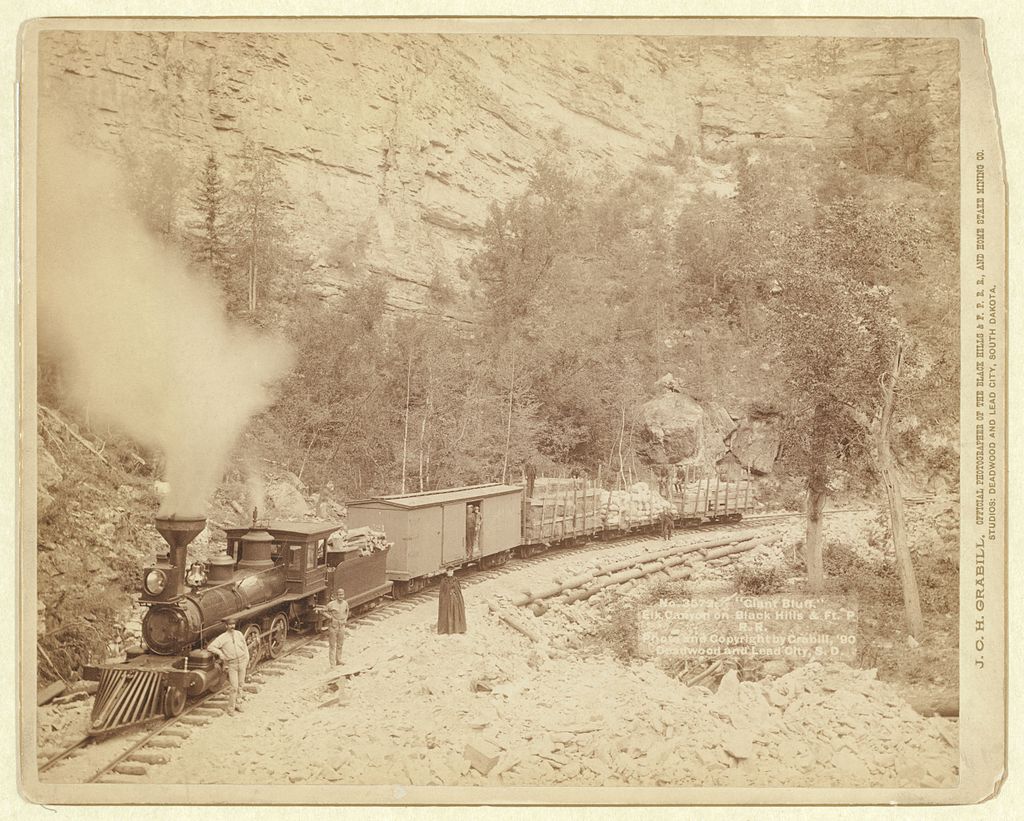

That option is called “HOn3” or HO scale trains running on tracks that are narrower than standard gauge. In HO scale, standard gauge is 16.5mm, but HOn3 trains run on tracks that are a scale 3ft (914mm) apart at 10.5mm gauge. I left out this option because there are some caveats with modeling HOn3. For one thing, modeling narrow gauge railroads is a niche market within the hobby. Unless you are modeling Colorado narrow gauge, finding prototype information is more difficult, finding prototypical rolling stock and locomotives are harder still. Most narrow-gauge railroads also ran in the 1880-1910 era which isn’t as popular as modeling the 1950s, 1970s, or even present day. The learning curve is higher as well since many models are only available in kit-form or there may not be a commercially available product at all for certain locomotives or rollingstock. This requires a high degree of model-building skill that a novice is unlikely to possess. Nonetheless, HOn3 does have a few advantages.

Benefits of HOn3

1. Saving Space

HO scale is great for the high potential of detail fidelity found on model trains. Even budget-minded rolling stock and locomotives have a good amount of detail included which a lot of models in larger scales lack. Not to mention that the latest generation of HO scale models have separately applied details that rival or exceed what scratch builders were doing two decades ago. However, the size of the trains gets to be an issue when it comes to building train layouts. Americans in particular have always been fond of building circuitous train layouts where the train can travel endlessly on a loop of some kind. Only recently has there been a movement in the states to build train layouts that run point-to-point using as few turnouts as possible to serve all the industries along the route. Authors such as Lance Mindheim have been promoting this design philosophy for years now and it has now begun to manifest itself in new layouts being built.

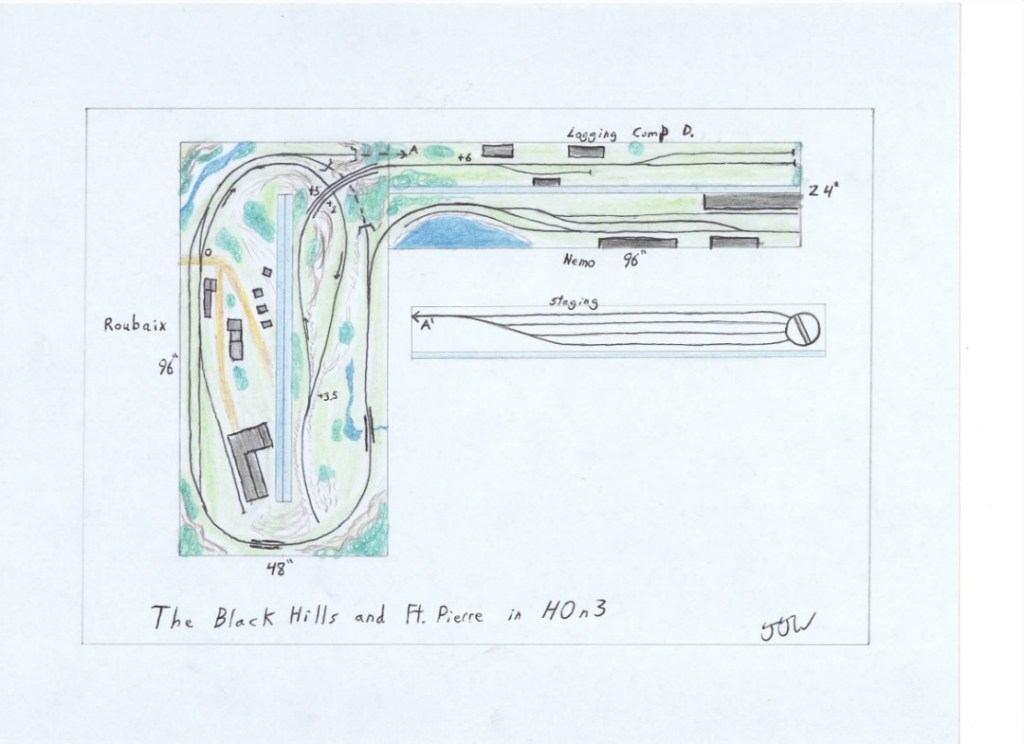

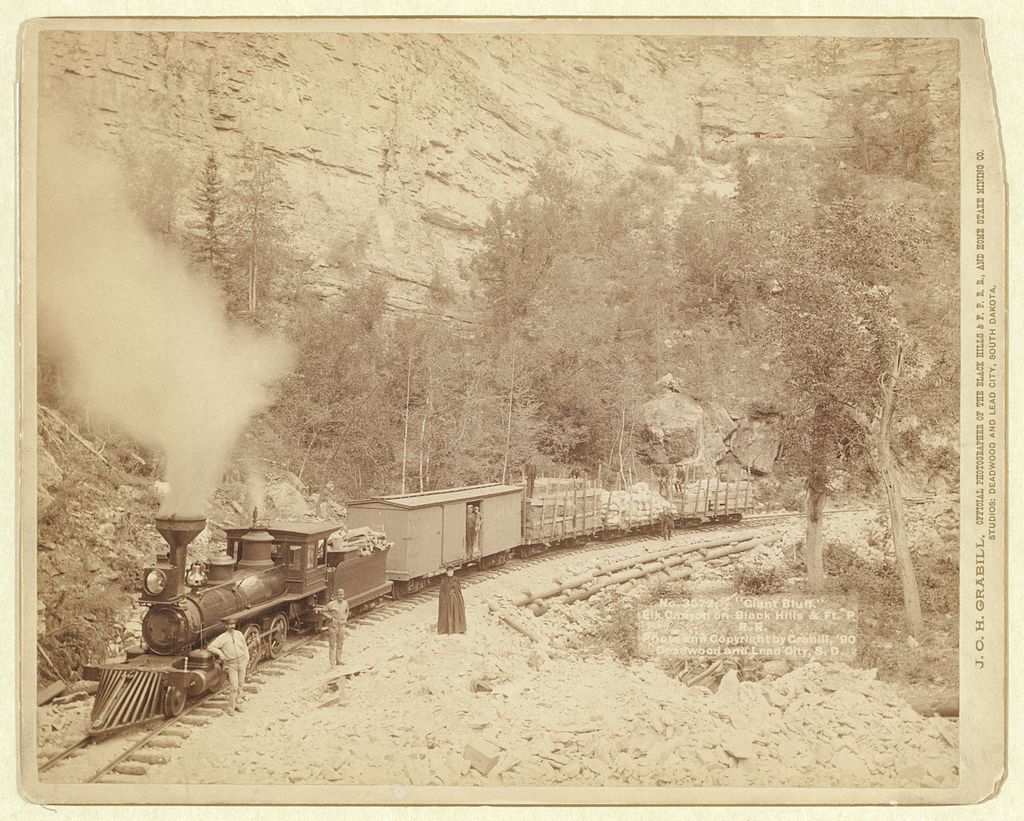

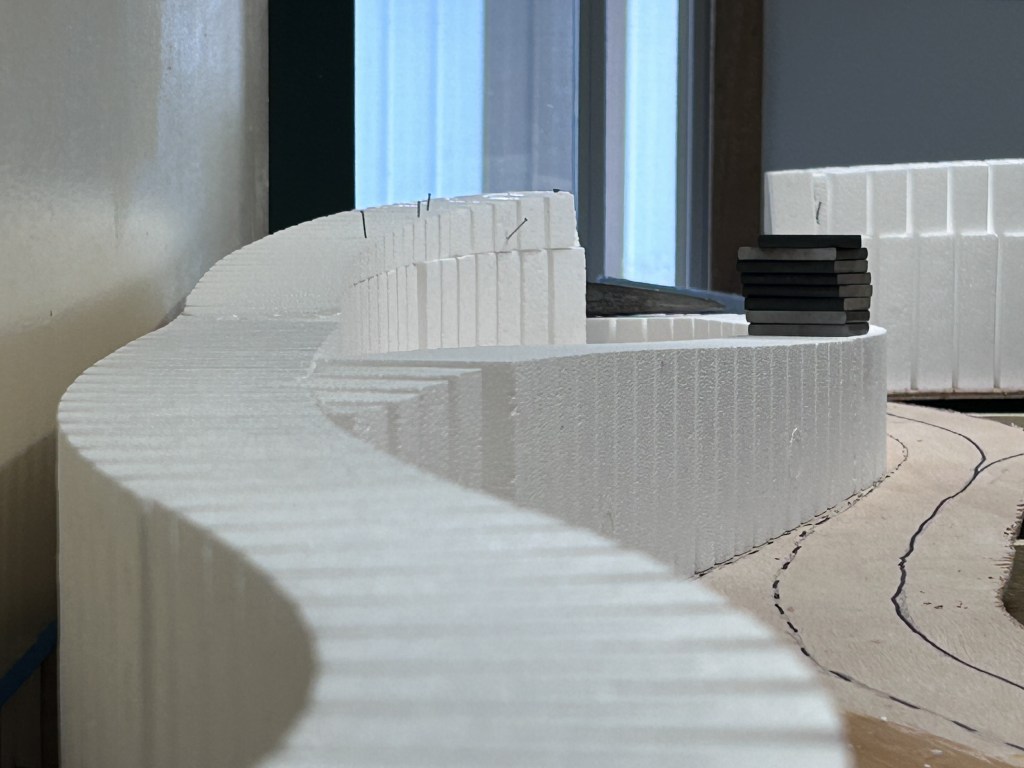

Even so, turn radius is a problem. Realistic curves in HO scale would be tens of feet in radius and the practical curves people end up using typically fall in a range of 20-30 inch radius. Train length is also a problem. A cut of twenty 50-foot boxcars in HO scale takes up about twelve feet of space! HOn3 on the other hand can comfortably use 18-20 inch radius curves and require much shorter sidings due to the shorter train lengths involved. A long narrow-gauge train (DRGW not withstanding) might only be a dozen cars or so. The Black Hills and Fort Pierre, which I model, had locomotives that could only pull about ten cars. Obviously, structures are going to take up the same amount of space as will roads, but narrow-gauge railroads often operated in hilly or mountainous terrain that was decidedly rural. That means fewer structures, fewer roads, and as much green scenery as you have room for!

2. Unique Prototypes

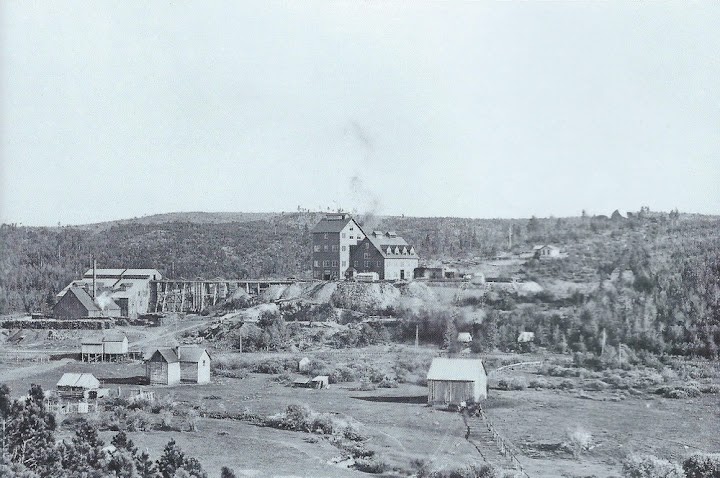

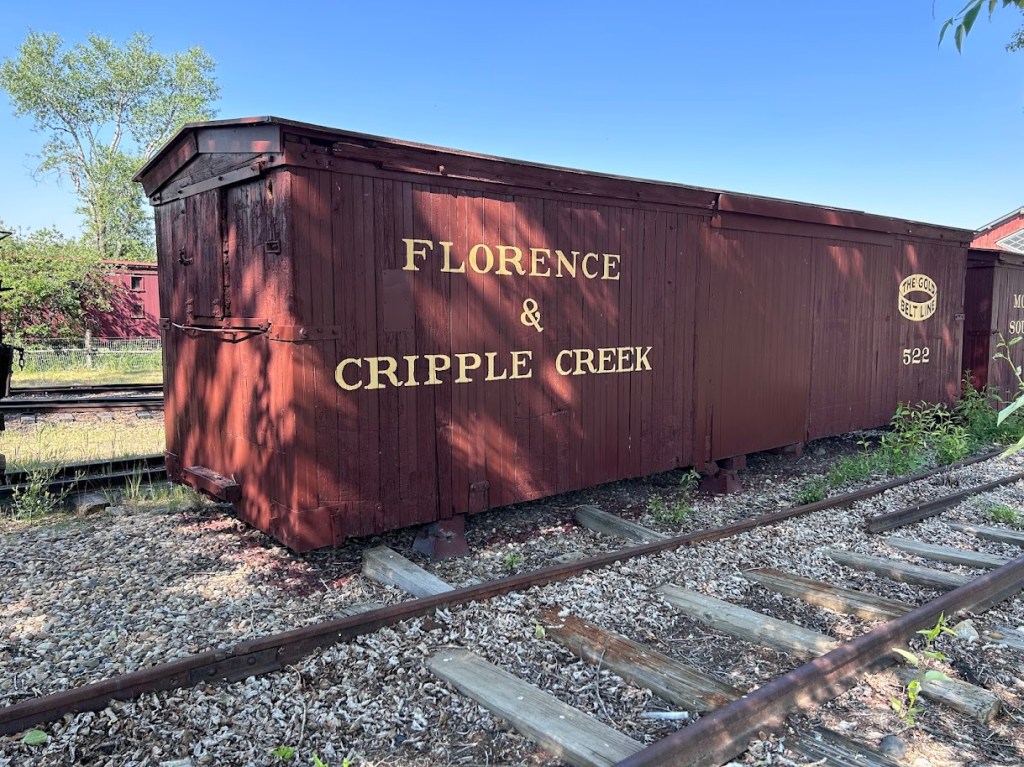

Perhaps it’s just a personal problem, but I’ve never had much interest in modeling railroads everyone else is already familiar with. Modern class I’s like BNSF and Union Pacific as well as fallen flags like the New York Central or the Pennsylvania railroad just don’t appeal to me beyond a generic historical context. You know what is fun? Taking the path less-worn or even forging a new trail completely! HOn3 has a lot of opportunities to explore prototypes that few people have ever even heard of. Montana Southern? Burlington and Northwestern? Oahu Railway and Land Company? All three were narrow gauge railroads operating in the Pioneer Mountains of Montana, the cornfields of Iowa, and the Big Island of Hawaii respectively. There are literally hundreds of narrow-gauge prototypes in North America and most of them were 3ft gauge. Even the more popular railroads on the narrow-gauge scene like the Denver and Rio Grande Western or Westside Lumber Company have a much smaller fanbase than the standard gauge class I’s from the last sixty years or so.

3. Art of Model Railroading

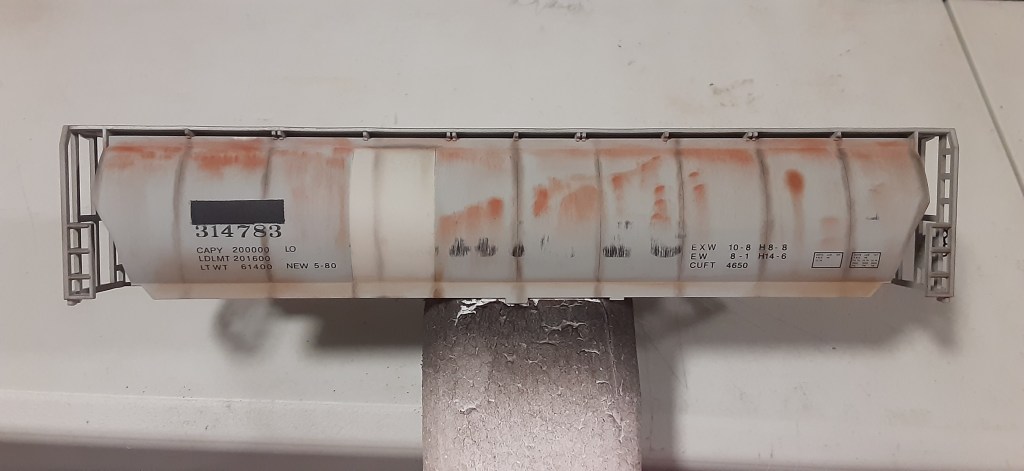

Okay, now while it is possible to view standard gauge model railroads as being works of art (looking at you, George Sellios!), there is something about narrow gauge which challenges hobbyists to get more creative with the scenery and detailing. Perhaps it’s the higher learning curve or maybe a side-effect of attracting people who want to physically make the most on their layout, but some of the finest model railroads to ever be created are HOn3. A prime example is Harry Brunk’s famous Colorado & Southern model railroad that now sits on display in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The layout was constructed over several decades by a master modeler and the end result is a model railroad like no other. These days it is easy to purchase ready-to-run models right off the shelf and run diesel locomotives that perfectly match the prototype. Heck, even recently Athearn admitted to making the egregious error of having the wrong light arrangement on one of their diesel models! Fifty years ago people were happy just to have a model of a locomotive at all but now this is grounds for a recall. That’s not a complaint, by the way. I think it’s amazing that a company admits to such a mistake and does whatever it can to correct it, but I digress. With HOn3, you have to make most things yourself or modify commercially available products. Outside of a couple of manufacturers, you aren’t buying ready-to-run models. Most people see that as a huge negative, in which case HO standard gauge is waiting with open arms. But for those who want to create, HOn3 provides a lot of opportunity out of necessity.

So, how do I get started in HOn3?

Now ain’t that the million-dollar question? And yeah, that number isn’t as far off as you might think! Getting started in HOn3 is no doubt more difficult than HO standard. For one thing, the only ready-to-run locomotives out there with DCC and Sound are made by Blackstone. Problem is that this company hasn’t really been making any new runs in the last several years and their product line is almost exclusively Colorado-based. Ther companies like Micro Engineering make track and turnouts, but that too is sometimes hard to locate. Micro Trains even did some rolling stock runs but haven’t made anything recently. Are you noticing a theme yet? If you want to get started in HOn3 model trains, you can’t just pop on over to the local hobby shop and get a train set.

Unlike with HO standard gauge, the best place to get started with HOn3 is to begin reading about prototype railroads. Train shows are a great place to find old books nice and cheap but Ebay, Amazon, and other digital marketplaces will have books about narrow gauge railroads as well. You can supplement your reading with videos on Youtube or from production companies like Green Frog videos. Regardless of your medium of information, the goal is simply to find what you like. The next step then is to figure out what products are available for your chosen prototype or for what matches the aesthetic you want to go for. You’ll be able to quickly put together a list of models to be on the lookout for.

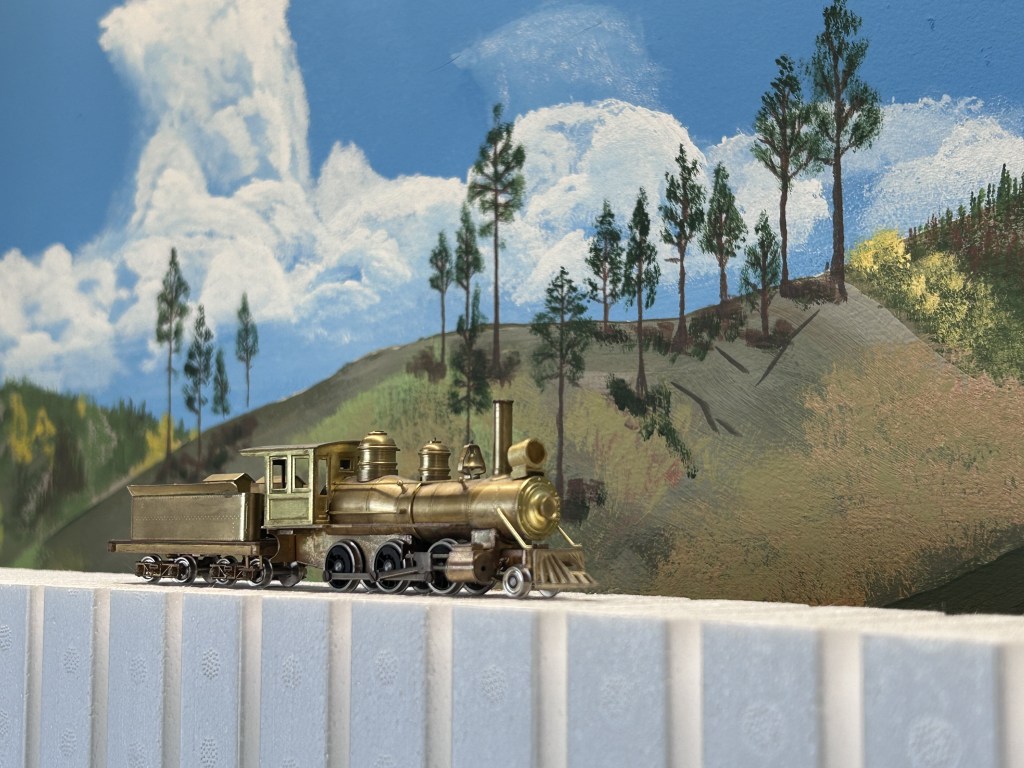

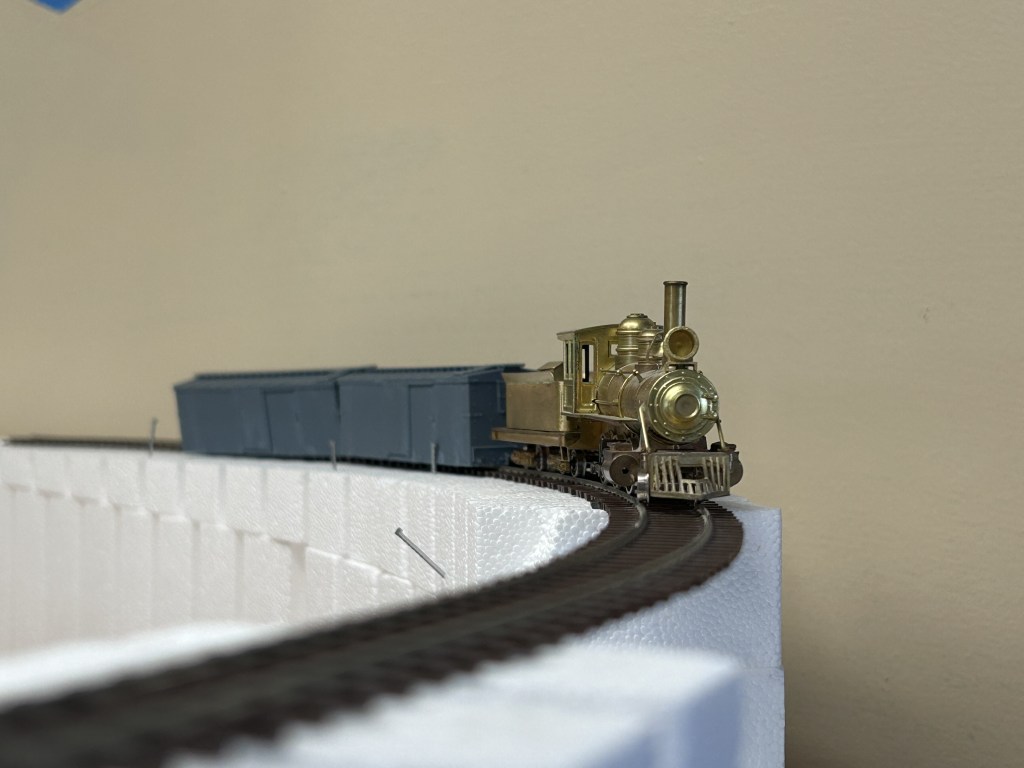

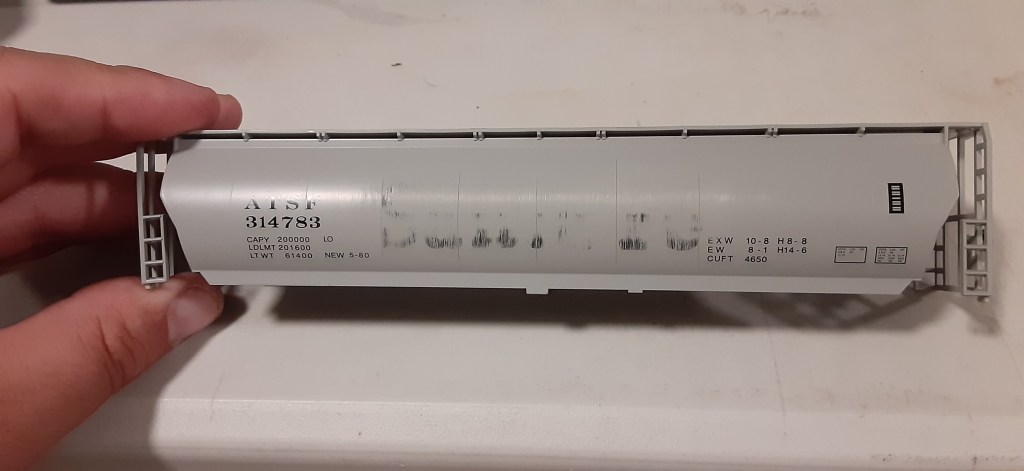

After that, my next suggestion is to save a bit of money to purchase a bit of track plus a Blackstone locomotive and a few cars that are either commercially made or have been built for you already. Throw in a DCC system as well. Why? Because at least this way you’ll have a nice-looking and smooth-running train to run while you accelerate up that learning curve! Now, the price tag for such a thing isn’t going to be cheap. In today’s dollars, expect to spend somewhere between $1200 and $2000. Yes, that’s quite the entry fee! The good news is that relative to other scales, you really aren’t spending more money. In fact, if you build most things yourself you’ll be coming out ahead in the long run because you need less equipment, less track, less buildings, and less space. On my home layout, almost everything is going to be built from scratch or from kits. Even my trio of brass 2-6-0’s only cost me an average of $250 each. The issue is I need to invest another $400 apiece to get them running smoothly with a modern can motor along with DCC, Sound, painting, weathering, and custom decals. The point is that you’ll be spending more time to save money after that initial plunge and in the end you’ll be a better modeler for it. To elaborate further and show my suggestions in action, I am actually planning a build series that focuses on this set-up as a starting point for someone new to HOn3. A simple layout with a minimum of equipment at a budget that most people can afford if they save money for a few months or a year.

Conclusion

You might be a bit disappointed with my sales pitch for HOn3, but if I’m honest that is kind of the point. There are advantages to HOn3, but several challenges as well. You can’t just go to a train show and pick up a bunch of five-dollar freight cars out of the bargain bin. Even if you do manage to find such a score, they will all be old kits that you have to build, paint, and make run reliably. Good engines are hard to come by, but when you find one you will cherish it and you’ll want to make the investment to make sure it runs better than anything a standard gauge modeler can get their hands on directly from a manufacturer. You’ll need to do some research as well, but this too will make you a better modeler and an amateur historian. And to supplement these high-quality models you’ll be building, you’re going to want to construct a more detailed, museum-quality layout. So really, HOn3 modeling and narrow-gauge modeling isn’t for the faint of heart. It requires money, time, and dedication to improving your craft. I’d say that for most people, this will be what turns them back toward standard gauge modeling. But for an intrepid few, HOn3 is a brand new canvas upon which they can create a masterpiece.